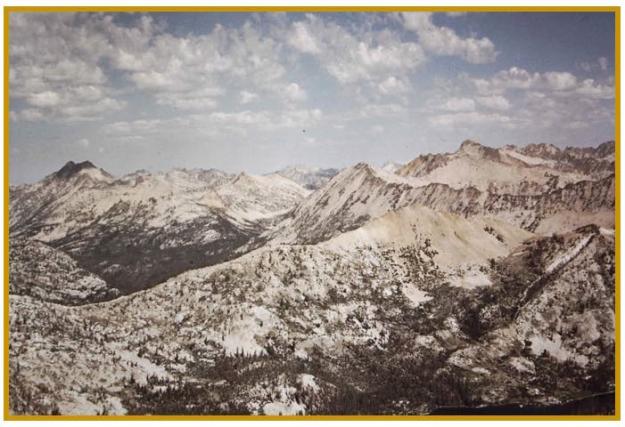

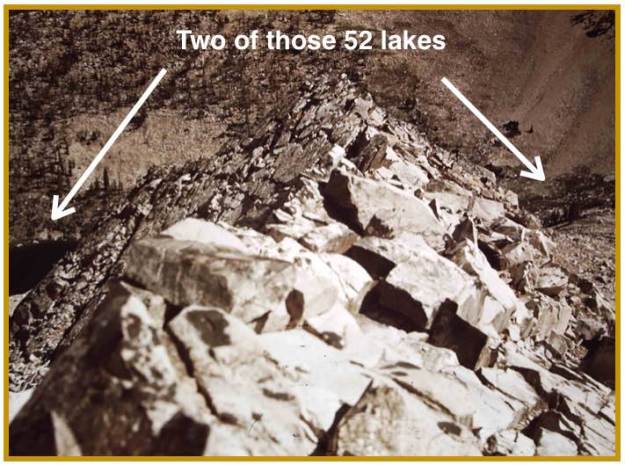

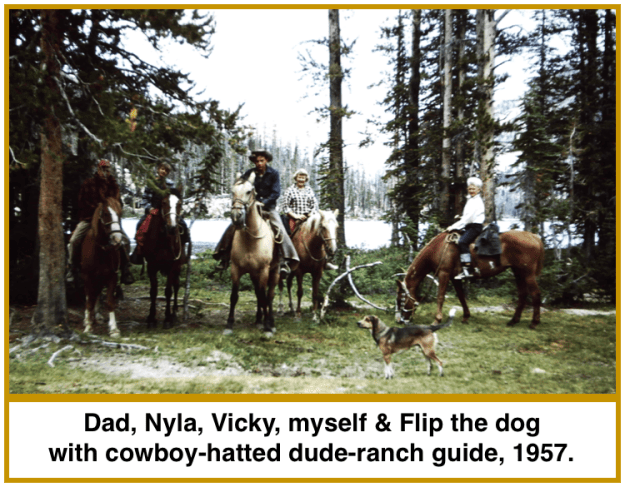

When we returned to the horses after our jaunt to the top of Snowyside Peak we stopped for a snack and then pointed the horses toward the northwest, heading toward Pettit Lake. It wasn’t long before we passed Twin Lakes and then came to a large flat area beside Alice Lake. We were a half mile lower in altitude than we had been when on top of Snowyside Peak and the winds were passing over us from the other side of the mountains. It was late afternoon on a sunny August day. Time to pitch camp.

We kids gathered wood from the ground and dead snags hanging from the trees. Mom got dinner going. Dad laid out the tarp on which we blew up air mattresses and made our beds from the blankets that had been piled on the saddle bags atop the horses.

Yep, we carried blankets, not sleeping bags. But we did not carry pillows — a rolled up coat served just fine and it kept the coat warm for getting up on cold August mornings above 8,000 feet. Another trick we learned early in our Sawtooth hikes was to stuff the next morning’s clothes under the covers with us. It sure beat having to pull on freezing pants and shirts in the morning!

Once we were settled in Dad pulled the second tarp up over our beds to under our chins to keep off the dew. I remember falling asleep to the oily smell of that 1950s canvas tarp mixed with the fresh pine and cold and purity of mountain air. Bright silver stars filled the blackest of black sky.

The next thing I knew was waking to the smell of that tarp completely over my head. I pulled back the tarp to find two inches of snow blanketing every feature of a bright, sunny summer morning.

Recommendations —

- Sasa Milo has an excellent post of his 2014 walk around the Alice – Toxaway Loop Trail, from which we accessed Snowyside Peak. His photos are way beyond what my dad was able to capture on the Kodachrome slides I have scanned for these posts. And he’s done a great job of capturing the little delights of the mountain trail as well as the majestic grandeur of the Sawtooth Mountains. His topographical map can’t be beat. CLICK HERE

• Here’s more on Fredlyfish4 who contributed the photo of Alice Lake.